Throughout history, many visionary artists have risen in their fields. Some of those visionaries go on to develop new practices, create amazing things, and even change the face of their art. Even fewer of those people have an impact so huge, that it changes the way their art is practiced forever. Those people we call genius, and Elvin Jones was that kind of genius.

“Your body is one, even though you have two legs, two arms, ten fingers, and all of that. All of those parts add up to one human being. It’s the same with the [drum set]. People are never going to approach the drumset correctly if they don’t start thinking of it as a single musical instrument.”

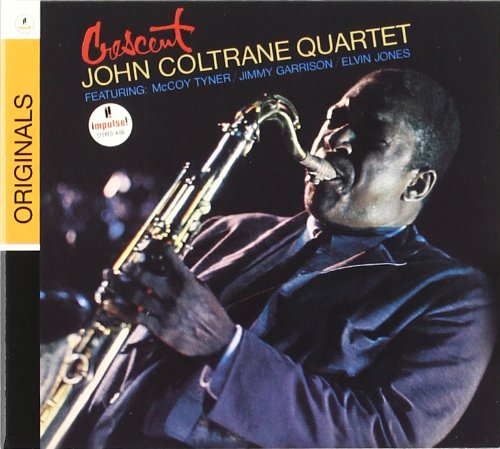

Jazz drummer Elvin Jones was born on September 9, 1927 in Pontiac, Michigan, into a family filled with music. Growing up in this environment, he had innumerable chances to listen to and play music. His illustrious older brothers, renowned trumpeter/bandleader/composer/arranger Thad, and fabulous pianist Hank, guided him through the local jazz scene they were already immersed in, and through it Elvin began to grow and blossom as a musician. After a three-year stint in the military, where he absorbed the marching and concert band traditions, Elvin moved to New York City and set up shop. He played the club scene throughout the city, working with some of jazz’s biggest names at the time, including Charles Mingus and, later, Sonny Rollins. The chance to play (and record) with Rollins was an important stepping-stone for Jones, as he was finally given the opportunity to stretch out and apply some of his new, interpretive musical ideas. Further continuing his growth and development of his style, Elvin met and first worked with saxophonist John Coltrane while in Miles Davis’s band. When Coltrane later went on to form his own quartet in 1960, Elvin enthusiastically joined on; a partnership that proved to be among music history’s most fruitful. Although Elvin enjoyed a lengthy career as a bandleader and sideman, among his best and most recognized work was done with Coltrane. During this time, he worked and recorded at the top of his game, appearing on many albums with Coltrane’s group, as well as sessions with other greats like Wayne Shorter. After many years and countless albums with the Coltrane quartet, Elvin left the saxophonist’s band in 1966, going on to start his career as a leader. His subsequent bands became known as the Elvin Jones Jazz Machine, and served as a proving ground for some of the music’s most promising talent.

Elvin Jones’ style is, to say the very least, all his own. He enjoyed massive success throughout his equally sizeable career: he recorded heavily with arguably the greatest quartet ever, and continued his life as an incredibly in-demand session drummer and bandleader. Part of what makes Elvin so unique is his approach to the drum set. He was among the first drummers to begin thinking of the drum set as one cohesive instrument, rather than a mere collection of tubs and plates. Elvin’s approach was to move the time not with a simple ride cymbal pattern or bass/snare combination, but to push the music forward using the entire kit. This fundamental element of his style can be heard in every facet of his playing, from his time feel, the way he approaches comping, and his soloing ideas.

Elvin’s time feel has been described as many things. Often times, the most common phrase used to make this description is “rolling triplets.” His uncanny sense of pulse and subdivision allowed him to stretch the boundaries of drum set timekeeping, and he was able to do this with his unique triplet-based approach. While always able to keep the pulse of the music intact, Elvin filled in the time – the spaces between beats of the pulse – with a series of triplets, broken up around different pieces of the kit. Often, this advanced rolling triplets concept was applied with a technique now known as “hand chasing.” This technique, used heavily by Elvin in his playing, relies on a strong pattern being played on the ride by the right hand, while other triplet partials are played on the snare with the left hand. The result is a broken-up sound, where all triplet partials are accounted for on either the ride or snare. Finally, he was famous for adding tension to the accompaniment by playing in 3 beat phrases within a 4/4 environment. This technique gave the music a lilting feeling, and allowed him to build the music to a polyrhythmic frenzy before climaxing on a solid beat one. Below are some examples of how Elvin would take the classic jazz pattern and make it his own by improvising with eighth note triplets. At the end, the hand chasing and the 3-over-4 phrasing techniques are illustrated as an application of the examples preceding it.

Beginning with a simple jazz pattern on the ride cymbal and hi hat, add the second two notes of the eighth note triplet to each beat.

Next, a variation of the first example: moving the third partial of the triplet from the snare onto the kick drum.

Next, move the ride cymbal pattern around to accentuate different partials of the triplet. Note the incorporation of both the snare drum and the bass drum on the third partial of the triplets.

Here we have an advanced example of some “Elvin time.” Note how the right and left hand incorporate the concept of hand chasing. Also, observe the manner in which the figure is phrased – it illustrates the 3-over-4 concept, repeating on a downbeat every three beats.

From the above examples, one can get a solid idea of where Elvin is coming from in his time feel approach. His playing incorporated any or all of those concepts to create a steadily flowing groove that would ebb and flow with the intensity of the soloist he was playing behind. This series of techniques illustrates another important facet of Elvin Jones’ playing. He was revolutionary in his ability to make the drumset – a combination of many different sound sources – sound as a single, cohesive, musical instrument. In the instrumental canon from which he was trained, the execution of musical ideas on the drumset was usually heavily reliant on the right hand (more specifically, the ride cymbal) to drive the time. This concept made the other limbs, and the instruments they were assigned to, less important to the overall pulse of the music; the hi hat, bass, and snare drums were added as mere colors and accents. Elvin’s approach to this concept, like so many others, was iconoclastic. “You can’t isolate the different parts of the drumset any more than you can isolate your left leg from the rest of your body.” Elvin said in an interview, “Your body is one, even though you have two legs, two arms, ten fingers, and all of that. All of those parts add up to one human being. It’s the same with the [drum set]. People are never going to approach the drumset correctly if they don’t start thinking of it as a single musical instrument.” Elvin developed this approach by orchestrating his rolling triplet patterns around all of the drums, filling up and pushing the time with one continuous drum set sound. It is this technique that is fundamental to the “Elvin sound,” and provided an intense sea of polyrhythm for a soloist to swim in.

While his time feel is what makes him great to listen to, his inspiring playing behind soloists is what makes him so prolific. While he burned behind the cream of the jazz crop, some of the best examples of Elvin’s virtuosic comping abilities are found in the recordings he made with John Coltrane. Jones’ burning intensity was the catalyst for some of Coltrane’s most celebrated improvisations, and aided him in creating some of the greatest jazz this world has ever known. Technically speaking, all of what Elvin played behind soloists was variations on the broken triplet and hand chasing concepts illustrated earlier. However, it was the application of those concepts that pushed the music’s energy to stratospheric levels, and encapsulated his revolutionary drum set style. Before Elvin, most drummers were relatively sheepish. Not to say that there were not fantastic players in their own right, but when playing with a band, most times the drummers were relegated to a more simplistic, understated time-keeping role. They had their solos and their moments of intensity, but generally stuck to the “spang-a-lang” cymbal patterns and some light snare chatter. Elvin Jones changed all of that. While the core of his playing was rooted in the drumming styles of old – after all, his early mentors included the likes of Max Roach and Jo Jones – his musicality was not limited to that style’s simplicity. Elvin was able to transcend the music in ways never before imagined, and take the art he created to a higher plane. His drumset, as a single voice, propelled like none other.

An Elvin Jones drum solo is, in so many words, a force to be reckoned with. If the power showcased in his comping was any indication, Elvin Jones could bash the drums with rock star quality when given the chance. Straying away from the traditionally rhythmic drum solos of his mentors, Elvin’s were exercises in intensity, passion, and melodicism. He incorporated many of the polyrhythmic ideas previously discussed, and coupled them with a dedicated, albeit sometimes abstruse, adherence to the melody of the song at hand. “I hear the tune in my mind, so I know where I am at any point in the composition. Of course, this has to be reflected in what the solo is stating, whether it be realistic or abstract, in tempo or out of tempo.” While his rhythmic explorations often sounded intensely out-of-time and even verging on completely free, they also can be applied to the melody with careful listening. Elvin interpreted melodies in his own way, and made drum solos something more than mere showcases of licks.

On May 18th, 2004, Elvin Ray Jones passed away. He continued to play the drums with his band, the Elvin Jones Jazz Machine, up until mere months before his passing. This serves as yet another indication of his intense passion and sense of servitude for the music that he adored; he could never leave the music, and the music could never leave him. He indelibly marked our time with his sophisticated, spiritual artistry, and will always be remembered. Even beyond his seventy-six years, Elvin Jones’ soulful musicianship will continue to reign supreme.